|

|

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

If you have a collector in

your family, welcome to the Georgia Rocks web site. Anyone can begin collecting

rocks, minerals, and fossils in Georgia (subject to respecting the rights of

landowners) without any knowledge of the geologic story behind them. But

investing a little time reading on this site or in Roadside Geology of

Georgia will add to your enjoyment,

wherever you go in the state. |

||||||||

|

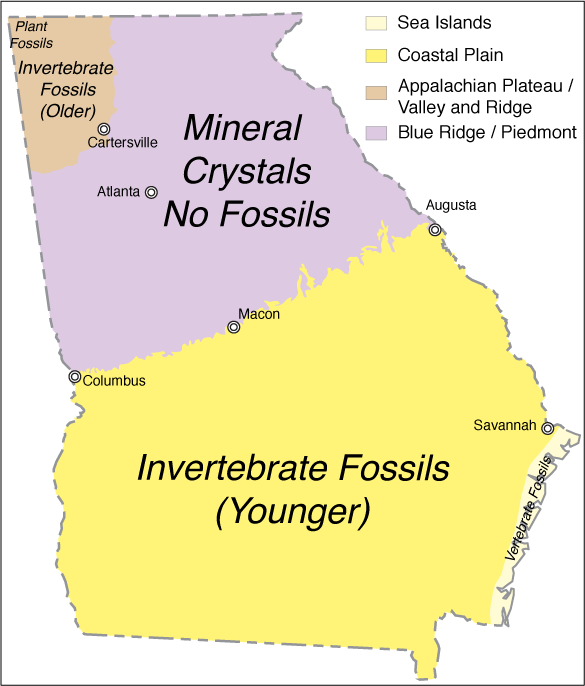

Before heading out, at least

look at a map that divides the state into three parts in which different

kinds of collecting are possible. In Georgia’s Blue Ridge/Piedmont region, no

fossil remains of organisms have yet been found, because rocks experienced

high heat and pressure (in some cases melting the rock). Those same

conditions, however, caused mineral crystals to grow that make attractive

specimens. |

|

|||||||

|

In the Valley and

Ridge/Appalachian Plateau region, the part of the state north and west of

Cartersville, a generally shallow sea existed at the same time that life was

evolving from the first invertebrates with hard body parts (e.g. trilobites),

through fish to the first amphibians and reptiles. You are quite likely to

find invertebrate fossils there, especially in the rocks known as shale and

limestone. Atop Lookout Mountain and Sand Mountain, shale layers also have

plant fossils. South of a line through Columbus,

Macon and Augusta is the Coastal Plain. Here, beginning at the time of the

dinosaurs (when sea level was much higher than today), the Atlantic Ocean

left behind sand, clay, and limestone. The fossils you find there are younger

by more than 100 million years than the youngest fossils in northwest

Georgia. Some dinosaur fossils have been found near Columbus, but you are far

more likely, especially looking in limestone, to find fossils of

invertebrates, many not very different from shells around the beach today. Along the coast, in addition

to modern seashells, look for bones and teeth that have often been blackened

by chemical processes during burial. These are fossils from a large variety

of vertebrates that lived at the same time as our early human ancestors, when

great ice sheets covered lands now part of the northern US and Canada. You

can also learn a lot about the trace fossils in ancient rocks – tracks,

trails, burrows – by examining those left literally yesterday by

organisms on the coast. See Life

Traces of the Georgia Coast, a new book by Emory University paleontologist

Dr. Anthony Martin, for more. In the book, and eventually

in notes added to the maps on this website,

you will find references to the kinds of fossils you are most likely to find

in particular strata. Invertebrate fossils and shark teeth generally can be

collected without problem, but vertebrate bone discoveries may be

scientifically significant, so check with qualified museum or university

personnel before disturbing them to avoid losing important scientific

information. For minerals in Georgia,

specific state publications are helpful. The Mineral Resource Map of

Georgia (Georgia Geological Survey, 1969),

and Minerals of Georgia (R.B. Cook,

1978), can be purchased online from

the Georgia Department of Natural Resources. The best mineral and fossil localities come and go,

with new localities uncovered by construction, and old localities succumbing

to erosion and collectors.

Observation and collecting are easy at many roadside exposures, but

elsewhere landowner permission must be obtained, and some private mines and

collecting sites charge a fee.

Attending collecting trips organized by groups such as museums, or local mineral clubs

associated with the Southeastern Federation of Mineralogical Societies,

is generally the best way to visit private sites, as they have experience

finding the best localities and will arrange permission. |

||||||||

|

|

||||||||